Featured

Deleveraging China’s debt—is the country ready?

The Chinese government wants to reduce its debt; however, with so many deterrents, it’s not certain if it can accomplish that.

On October 18th of this year, the stock market cheered as Chinese micro-lender Qudian (QD) launched its $900 million-dollar initial public offering. Qudian services the insatiable demand that exists in China for short-term on-line unsecured “micro-loans.”

Its IPO was heralded as one of the most significant U.S. listings this year coming from China.

According to its filing: Qudian “target[s] hundreds of millions of quality, unserved or underserved consumers in China.” Lending money to, “young, mobile-active consumers who need access to small credit for their discretionary spending but are underserved by traditional financial institutions.” In other words, they lend small amounts of money at high rates to dodgy borrowers who want to buy things on Alibaba.

But despite its questionable business model, the company had an impressive public debut and was the biggest percentage gainer that day on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE); when its American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) priced at $24 per share, the soared 40 percent to $34.35.

But, as the saying goes “what goes up, must come down;” and for Qudian, this adage proved true at an alarmingly fast rate. In a matter of weeks, the ADRs of Qudian, as well as other Chinese quick loan lenders, plummeted from concerns by Chinese regulators over the high-interest rates charged on micro-loans that can exceed 35 percent.

The Chinese government addressed these concerns by suspending the regulatory approval for new online micro-loan companies; sending Qudian down 20% on November 21st, from its high price of $35; before crumbling to around $11, where it sits today.

Indeed, cracks are appearing in Chinese markets with the Shanghai/Shenzhen suffering a 300-point drop of almost 5% over the Thanksgiving Holiday. Stifling new guidelines have also created a rout in the bond market where yields on government treasury bonds rose to three-year highs; the yield on the Chinese-10 year has risen from about 3.6 percent in early October, to over four percent recently, which is a three-year high.

Many of these new rules were developed to minimize risks in the highly unregulated Asset Management industry that has ballooned in the past few years. According to the Peoples Bank of China (PBOC), at the end of 2016 the collective outstanding volume of the Asset Management business was 102 trillion yuan ($15.38 trillion); that includes 29 trillion yuan of bank wealth management products and 17.5 trillion yuan in trust products.

But, reining in the wild west of Chinese credit will undoubtedly bring turmoil to banks and millions of small investors. The new regulations will set leverage limits for Asset Management products, prohibit investors from pledging shares as collateral to obtain financing, and will discourage financial institutions from providing investors with implicit guarantees against investment losses. Furthermore, they constrain financial institutions from continually rolling over products–papering over investment losses by the new product issuance–a.k.a. a Ponzi scheme.

All these new regulations will likely cool the debt-fueled Chinese economy, which Deutsche Bank has recently noted is already losing heat. According to Deutsche, for the first time since Q4 2004, fixed asset investment growth has turned negative in real terms. In addition, the growth of property sales also turned negative in October for the first time since 2015.

New rules aimed to reduce leverage levels, curb asset price bubbles and rein in shadow banking will undoubtedly put a dent in China’s already reduced growth rate.

Now that General Secretary Xi Jinping has been anointed as China’s veritable King and bequeathed another five-year term, one has to wonder if this time China will finally make good on its promise to convert to a service-based economy and wind-down the debt and asset bubbles that were built up during his tenure.

How bad has China’s debt problem become? According to Gadfly, as Xi took office at the end of 2012, 986 non-financial state-owned enterprises (SOE’s) held roughly $2 trillion in assets with $775 billion in equity. Since then, those assets have swelled to $3.6 trillion, with only$ 1.25 trillion in equity–driving financial leverage up 286 percent. And, an analysis by Reuters of over 2,100 China-listed firms showed total debt at the end of September jumped by 23% from the year prior, which is the fastest growth since 2013.

In August of this year, The International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned that ending Chinese state companies’ debt addiction would require sweeping shifts in the way capital is allocated. But in the past, China’s solution to indebted SOEs has been to merge them into ever-bigger ones or infuse small amounts of private capital while keeping these monstrosities firmly in state hands.

The IMF isn’t the only one who is on to China’s debt shell game. S&P Global Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service both downgraded China’s sovereign rating this year over its continuous and intractable buildup of debt.

It is evident that China needs and wants to deleverage—at least for right now. But, what is less clear is if China has the stamina to go through with what will be a harrowing process. After all, other attempts to rein in debt-even though half-hearted-have failed miserably. As China is feigning this latest iteration of deleveraging, the entire world is becoming more wrapped up in China’s debt-fueled bubble.

© Michael Pento

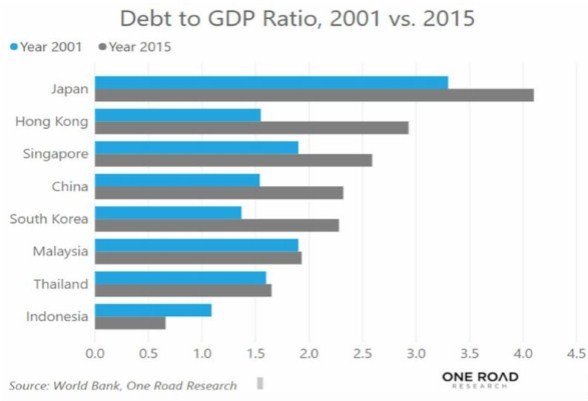

In fact, the entire Asia Pacific region is fueled by credit, which is, in turn, a function of the Sino debt-scam emanating from Shanghai. But it’s not just Asia that leans on Communist Debt; China is Europe’s and the United States second largest trading partner. The rise in China’s debt grew from $7 trillion in 2007 to nearly $30 trillion today, which happens to be the greatest increase of debt in the history of the world in any ten-year timeframe.

Of course, the massive increase in leverage didn’t represent honest savings that were carefully lent to the private sector to increase productivity. Rather, it was simply communist directed hole digging and filling. Given these painful imbalances, is it really credible to believe the air can be gently let out of this debt balloon with impunity? Not at all! This means Xi Jinping will have to abort this latest attempt very quickly, probably once the Shanghai Composite Exchange breaks below 3,000.

But, China is not alone in this game. Governments and central banks will never voluntarily be able to extricate from the humongous debt and asset bubble traps. This is because the global economy will descend into a deflationary depression without their constant heroin injections. They will instead be forced to borrow and print money until their citizenry reject fiat currencies en masse and runaway inflation engulfs the world. Sadly, time is quickly running out in the global middle class.

(The chart is courtesy of World Bank, One Road Research)

—

DISCLAIMER: This article expresses my own ideas and opinions. Any information I have shared are from sources that I believe to be reliable and accurate. I did not receive any financial compensation in writing this post, nor do I own any shares in any company I’ve mentioned. I encourage any reader to do their own diligent research first before making any investment decisions.

-

Impact Investing2 weeks ago

Impact Investing2 weeks agoThe Sustainability Revolution: Driving a Net-Zero, Nature-Positive Economy

-

Business9 hours ago

Business9 hours agoEchoes of 1929: Inflated Valuations and Warning Signs in Today’s Dow

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoTopRanked.io Weekly Affiliate Digest: What’s Hot in Affiliate Marketing [EKSA Affiliate Program Review]

-

Impact Investing5 days ago

Impact Investing5 days agoOceanEye: EU Launches €50 Million Initiative to Strengthen Global Ocean Monitoring

You must be logged in to post a comment Login