Cannabis

New York’s Approach to Cannabis Legalization Isn’t Working

New York’s approach to cannabis legalization includes a complex licensing system aimed at promoting equity by prioritizing licenses for individuals most affected by the war on drugs. However, frequent changes in application processes and high operational costs have limited legal market entry, favoring larger investors with significant capital. The result is a proliferation of unlicensed stores.

Over the last twelve years, dozens of American states have legalized recreational cannabis. Colorado and Washington led the way in 2012, with Florida, Idaho, Nebraska, and South Dakota possibly following suit if voters approve legislative proposals in the November elections. In New York, legalization has been gradual: in 2019, Governor Andrew Cuomo decriminalized the possession of small amounts of cannabis for recreational use, which until then could lead to imprisonment. This change allowed approximately 600,000 previously arrested individuals to seek a review and amendment of their criminal records.

Download the free Born2Invest news app for more of the latest cannabis news.

The 2021 Legislation

In 2021, a law fully legalizing cannabis took effect, permitting individuals over 21 to possess up to 3 ounces (about 85 grams) and to grow up to six plants for personal use. Today, the pervasive scent of cannabis at nearly every intersection in New York underscores how normal and accepted public consumption has become.

Licensing Challenges

However, deciding who gets the right to open an authorized recreational cannabis store has been significantly more complicated. While many states opened their markets to any company or individual with the capital and desire to invest post-legalization, New York established the Office of Cannabis Management (OCM) to oversee the CAURD program (“Cannabis at Retail by Adults under Certain Conditions”). This program aimed ambitiously to initially grant most licenses to individuals disadvantaged by the “war on drugs”—a harsh federal campaign that disproportionately affected ethnic minorities, leading to the incarceration of thousands of African American youth. A portion of the taxes collected from authorized stores was also intended to be reinvested into further social programs for these marginalized communities.

Implementation Issues

Over the last three years, the implementation of the CAURD program has been fraught with difficulties, leading Governor Kathy Hochul in March to label it a “disaster” and dismiss the department’s director, who will leave in the fall. The guidance on application timing, costs, and methods has frequently changed, with the schedule further disrupted by a court order temporarily blocking parts of the program for not adhering to the text of the 2021 law.

\As a result, currently, there are only 85 authorized cannabis stores statewide, with over two thousand operating illegally in New York City alone, not waiting to apply for and receive a license.

The Roots of New York’s Cannabis Policy

Understanding why New York opted for an approach centered on equity and socioeconomic reintegration requires a look at history. Until 2019, possessing a small stock of cannabis was not a problem in New York State, but smoking it or even being seen in possession of it in public was illegal under a 1977 law. For decades, this law did not lead to significant consequences: the number of people arrested annually for public possession rarely exceeded a thousand, and in 1992 there were only 722. However, the situation changed with Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s administration in the 1990s, which encouraged the “stop-and-frisk” practice: police could stop anyone on vague suspicions and ask them to empty their pockets, leading to arrests if cannabis was found.

Disproportionate Impact on African Americans

This practice particularly affected young African Americans, who were statistically stopped far more often than their peers of other ethnicities: between 2002 and 2017, it was 12 times more likely that a Black New Yorker would be arrested for cannabis possession than a white one. This issue was frequently raised by organizations and campaigns against racism in the following years, and many New Yorkers (a city that tends to be politically more progressive than much of the rest of the United States) began to see the legalization of cannabis not only as a personal freedom issue but also as a way to remedy, at least in part, the damage and years of imprisonment inflicted on marginalized communities.

Economic and Social Dynamics of Legalization

The 2021 law, in addition to legalizing recreational cannabis, stipulated that 40% of the fiscal revenues related to cannabis sales be reinvested in communities where police had disproportionately carried out drug possession arrests, and aimed to assign half of all sales licenses to women, non-white people, disabled veterans, struggling farmers, and residents of overcrowded neighborhoods. The CAURD program introduced further restrictions, initially issuing licenses only to individuals previously incarcerated for cannabis possession or their family members.

According to a report published in March, however, many executives at the Office of Cannabis Management had never previously led a regulatory agency and pursued goals in a chaotic manner. For instance, they changed the application process so often that 90% of applications were sent back at least once for formal corrections.

The Struggle with Legalization’s Structure

As Jia Tolentino explained in The New Yorker, “investing in legal cannabis is typically a sport for those with substantial capital.” Opening a store can cost millions of dollars, and taxes are particularly high because cannabis remains illegal at the federal level, so owners cannot claim refunds for most of their business expenses. The 2021 law also prohibited vertical integration—meaning a single company could not own the cultivation, distribution, and stores, essentially controlling the entire supply chain—and required companies already in the medical cannabis market to wait three years from the passage of the law before they could apply for a license.

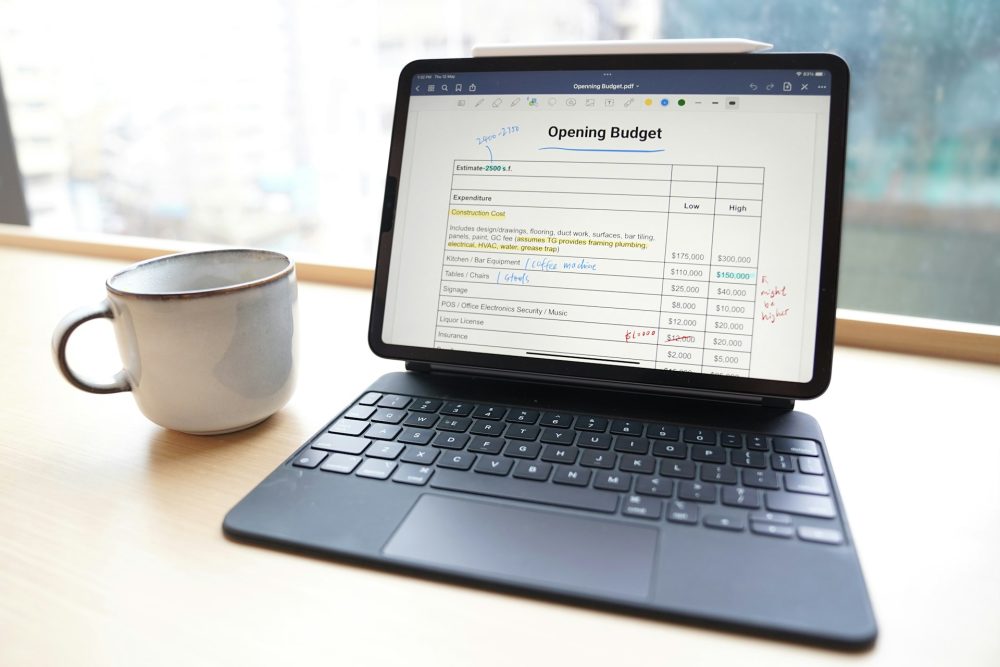

The CAURD was supposed to help small entrepreneurs enter the industry by offering store spaces at advantageous prices and access to a $200 million fund, but none of this materialized. The cost of merely applying for a license was $2,000, non-refundable even if refused. Furthermore, the new law did not provide a pathway for those involved in the black market to transition to the legal market, thus excluding many traders and growers who had never been arrested.

A Tale of Two Markets

By early 2022, about 900 people had applied for a license: only 36 were approved. The first legal cannabis store in the state opened on December 29, 2022, near Washington Square Park in New York. Tolentino reports that “the line spanned an entire block.” “As 2023 began,” she summarizes, “New York therefore had one authorized store selling weed and about 1,400 places doing the same thing illegally.”

Illegal stores vary greatly in appearance: some are spacious, well-lit, and clean in a way that somewhat resembles an Apple retail outlet, while others have replaced the small and characteristic neighborhood bodegas, thus being small, chaotic, and seemingly shady. Many have also appeared in other states where cannabis has been legalized: for example, in California, it is estimated that about half of the cannabis produced by legal growers is introduced into the illegal market.

The Unregulated Market’s Explosion

“The explosion of unlicensed weed stores in New York City, however, is unmatched,” writes Tolentino. “This is due, among other things, to the vast number of stores and the city’s hyperactive entrepreneurial culture, where vending machines are perpetually in bloom. But also to the fact that the city police no longer have the right to search cars or people on suspicion of smelling ‘cannabis,’ and thus seem to have lost all interest in monitoring its use.” In theory, illegal stores can be sanctioned in various ways. In practice, however, the rare times they are fined or raided by police, the owners close for a few days and then reopen shortly after.

__

(Featured image by Troy Jarrell via Unsplash)

DISCLAIMER: This article was written by a third party contributor and does not reflect the opinion of Born2Invest, its management, staff or its associates. Please review our disclaimer for more information.

This article may include forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements generally are identified by the words “believe,” “project,” “estimate,” “become,” “plan,” “will,” and similar expressions. These forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks as well as uncertainties, including those discussed in the following cautionary statements and elsewhere in this article and on this site. Although the Company may believe that its expectations are based on reasonable assumptions, the actual results that the Company may achieve may differ materially from any forward-looking statements, which reflect the opinions of the management of the Company only as of the date hereof. Additionally, please make sure to read these important disclosures.

First published in Il Post. A third-party contributor translated and adapted the article from the original. In case of discrepancy, the original will prevail.

Although we made reasonable efforts to provide accurate translations, some parts may be incorrect. Born2Invest assumes no responsibility for errors, omissions or ambiguities in the translations provided on this website. Any person or entity relying on translated content does so at their own risk. Born2Invest is not responsible for losses caused by such reliance on the accuracy or reliability of translated information. If you wish to report an error or inaccuracy in the translation, we encourage you to contact us

-

Cannabis1 week ago

Cannabis1 week agoCannabis and the Aging Brain: New Research Challenges Old Assumptions

-

Africa2 weeks ago

Africa2 weeks agoUnemployment in Moroco Falls in 2025, but Underemployment and Youth Joblessness Rise

-

Crowdfunding5 days ago

Crowdfunding5 days agoAWOL Vision’s Aetherion Projectors Raise Millions on Kickstarter

-

Fintech2 weeks ago

Fintech2 weeks agoFintower Secures €1.5M Seed Funding to Transform Financial Planning