Featured

Is the recession upon us? Think global synchronized bond collapse

Despite a rise, an expert believes that the slight increase in recent stocks will only contribute to the economic fluctuations leading to a bond collapse.

We have all heard, in ad nauseam fashion, Wall Street’s current favorite mantra touting a global synchronized economic recovery. For the record, global GDP growth for 2017 was 3.7 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund. And, although this is an improvement from recent years, you must take into account that in 2004 it was 4.4 percent, in 2005 it was 3.8 percent, in 2006 it was 4.3 percent, and in 2007 it was 4.2 percent. The point being, it’s not as if the current rate of global growth has climbed to a level never before witnessed in history — it’s not even close.

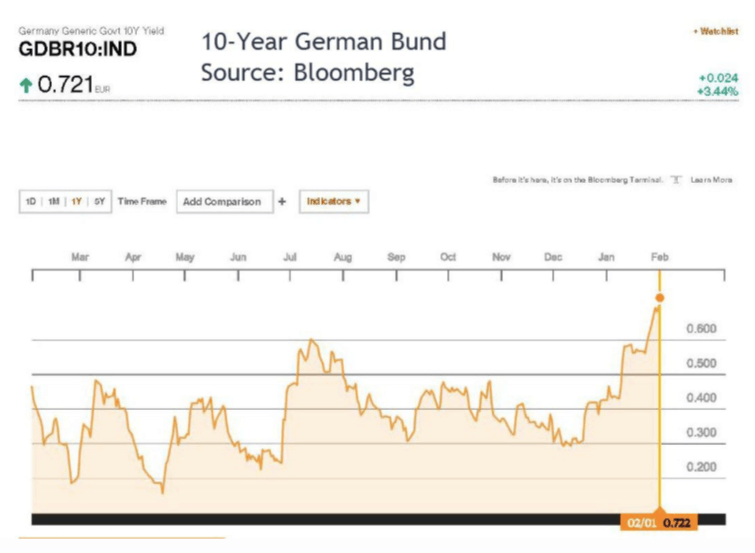

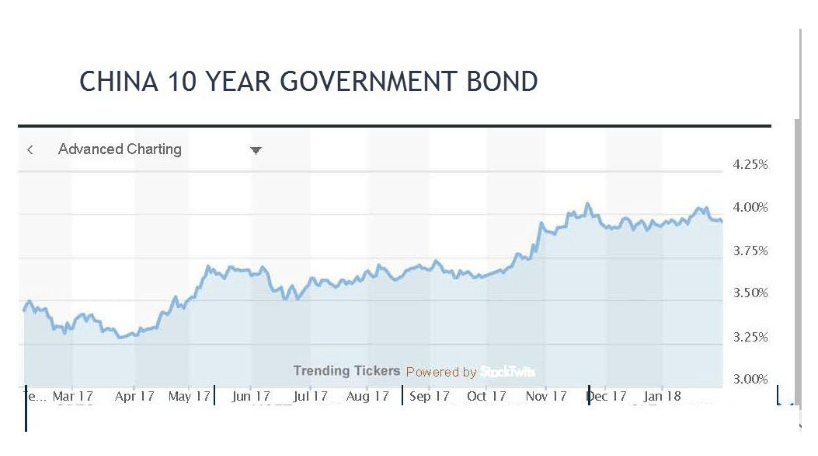

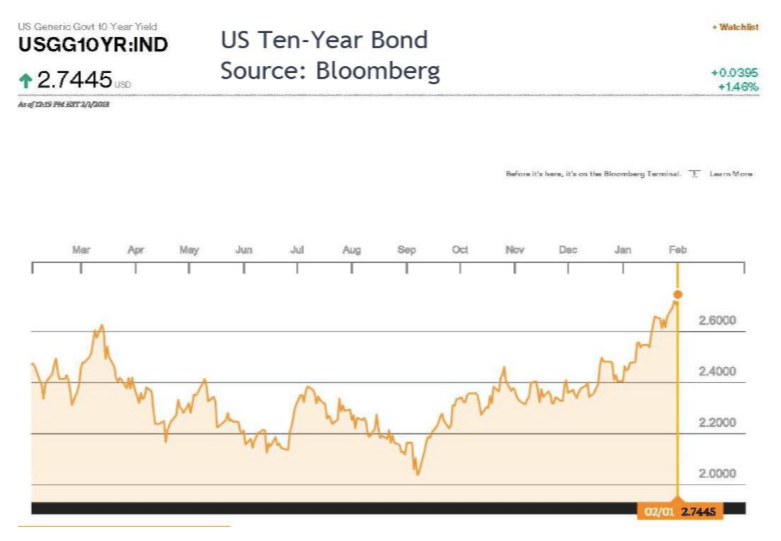

However, the more salient phenomenon now underway — far more important than the rather pedestrian move higher in global GDP — is the globally synchronized bond collapse, which the Main Stream Financial Media is dismissing with alacrity. Yields are on the move higher around the world and the rate of change is now escalating.

Therefore, as Wall Street is busily pricing the Trump Tax cuts into shares multiple times over, none of the bond bubble catastrophes is even getting a passing fancy. S&P 500 operating earnings, which removes all blemishes from a company’s performance, were $130 for 2017, and are projected to be $150 for 2018, which would amount to a 15 percent increase if achieved. But at 26-time GAAP earnings and 21.5-time trailing earnings — and even at 18.5 times next year’s ex-items earnings — the S&P 500 is pricing in a euphoria that is egregiously outlandish even for the carnival barkers on Wall Street.

It’s hard to come up with a better example for the market’s latest bubblelicious hysteria than Netflix. The company is projected to post operating free cash flow of about negative $9 billion over the five years ending in this year. Meanwhile, its market cap has soared well over $100 billion. At a PE ratio above 200, Netflix is burning through billions of dollars in cash each year. Yet, its billions of dollars’ worth of bonds are rated B+ by S&P. And incredibly, the yield the company is paying on that debt isn’t too much above a longer-term Treasury note!

But back to the current bond debacle and the unbridled enthusiasm over Trump’s unpaid for spending sprees. It’s always a great idea to give the private sector more of its own money. However, by cutting taxes and forgetting about the spending side of the ledger, what D.C. has done is hand money to corporations and individuals with one hand and immediately taking it back by increased Treasury issuances. And one of the necessary consequences of selling significantly more government debt is that yields must rise. That is especially true when debt is already at record levels, and bond prices are in the greatest bubble in the history of bubbles.

The other side of that tax cutting ledger is rising debt service costs. The annual interest expenses of non-financial corporate debt will rise by $37 billion in 2019. And that is assuming the Fed Funds Rate only reaches 2.15 percent; and the 10-year Note yield does not increase much further. This is according to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve itself. This presumably-mild rise in interest rates will wipe out nearly 37 percent of the corporate tax break of $100 billion per annum.

That is, as already stated, if long-term rates don’t rise — but they already are. And with global QE going from $170 billion per month to virtually zero come October, the incipient drop in bond prices is about to cascade violently.

Investors piled into U.S. bond mutual funds like never before in the wake of the Great Recession. That total rising to $4.6 trillion in November of 2017, from $1.5 trillion a decade earlier, according to the Investment Company Institute. The Central Banks’ strategy of buying sovereign debt in massive quantities until the yield offered next to nothing — and in many cases less than that — served to crowd out private investors and pushed them toward riskier bonds in a desperate search for an after-tax, real return on their fixed-income investments.

Therefore, when the central bank bids disappear come this fall, the $230 trillion worth of global debt will have to stand on its own wobbly feet for the first time in many years. For example, the Italian 10-year note offered a yield of 7 percent back in 2012 when its debt to GDP was “just” 123 percent. And before Mario Draghi vowed to do “whatever it takes” to keep European bond yields in check. Today, that debt has jumped to 132 percent of the economy, yet the yield has dropped to 2.03 percent. What investors are now forced to ponder is how high and how rapid bond yields will soar as the ECB removes its humungous and protracted bid from the bond market.

In like manner, who is going to want to own a U.S. 10-year Note that yields 2.7 percent when the average was well over 7 percent from the years 1971-2000? Those years are the important ones to analyze because it was after the Fed closed the gold window; and yet before it became completely committed to manipulate the yield curve towards 1 percent, or less, in order to ensure the business cycle was abrogated.

Interest rates are about to become unglued in a big way as this bond bubble explodes. Especially now that the Fed will be selling $600 billion of its balance sheet an annual rate come this fall; just as deficits climb to north of $1 trillion and the total U.S. debt has risen to 350 percent of GDP.

Therefore, as the global synchronized fixed-income fiasco picks up momentum, individual investors will be expected to supplant those erstwhile buy orders from the central bank. However, with the U.S. personal savings rate near an all-time record low, bond buyers will be few and far between. And as risk premiums become paper thin, the stock market will fall precipitously; just as junk bond yields begin to soar. This will slam the borrowing door shut on high-yield issuances and send these debt-dependent companies into a tailspin. At the same time, every asset that was priced off of those “risk free” sovereign bond yields, which provided countries the privilege that could only be expected in the twilight zone, i.e., to make money by borrowing money, will head into a nosedive as well.

Hence, the next recession is rapidly approaching. And one can see it clearly when viewing in plain sight the beginning of a bear market in bonds and its pernicious effect on insolvent companies and countries alike.

—

DISCLAIMER: This article expresses my own ideas and opinions. Any information I have shared are from sources that I believe to be reliable and accurate. I did not receive any financial compensation in writing this post, nor do I own any shares in any company I’ve mentioned. I encourage any reader to do their own diligent research first before making any investment decisions.

-

Fintech1 week ago

Fintech1 week agoSwissHacks 2026 to Launch Inaugural Swiss FinTech Week in Zurich

-

Cannabis4 days ago

Cannabis4 days agoColombia Moves to Finalize Medicinal Cannabis Regulations by March

-

Crowdfunding2 weeks ago

Crowdfunding2 weeks agoReal Estate Crowdfunding in Mexico: High Returns, Heavy Regulation, and Tax Inequality

-

Cannabis1 week ago

Cannabis1 week agoSouth Africa Proposes Liberal Cannabis Regulations with Expungement for Past Convictions

You must be logged in to post a comment Login