Featured

LIBOR is making a comeback in global banking system

LIBOR stands for London Interbank Offered Rate. It is the average interest rate estimated by banks in order to borrow money from one bank to another.

LIBOR, or the London Interbank Offered Rate, was the most important acronym most investors never heard of before 2008. However, it quickly became the most critical variable in markets leading up to the Great Recession.

What has now become clear is that we haven’t learned any lessons from the financial crisis except how to accumulate more debt and to artificially control markets more extensively. And, to conveniently try to sweep under the rug the very same warning signs that forebode the day of reckoning just over a decade ago.

Today, the mainstream financial media is obsessed with inane Congressional hearings surrounding Facebook—as if it were a surprise to users that the company’s privacy policy is to invade it—rather than talking about the more salient issues, like LIBOR.

In layman’s terms, LIBOR is the average interest rate required by leading banks in London to lend to one another. It originated in 1969 when a Greek banker by the name of Minos Zombanakis, arranged an $80 million syndicated loan from Manufacturers Hanover to the Shah of Iran. Zombanakis constructed the loan using reported funding costs derived from a group of reference banks in London. Other banks began tying debt to this rate, and by the mid-1980s the British Bankers’ Association took control of this new rate that we now refer to as LIBOR. Today, the banks that encompass the LIBOR panel are the most significant and creditworthy in London.

LIBOR performs two major purposes for today’s markets. First, it serves as a reference rate used to establish the terms of financial instruments such as short-term floating rate financial contracts like swaps and futures. It also serves as a benchmark rate–a comparative performance measure used for investment returns.

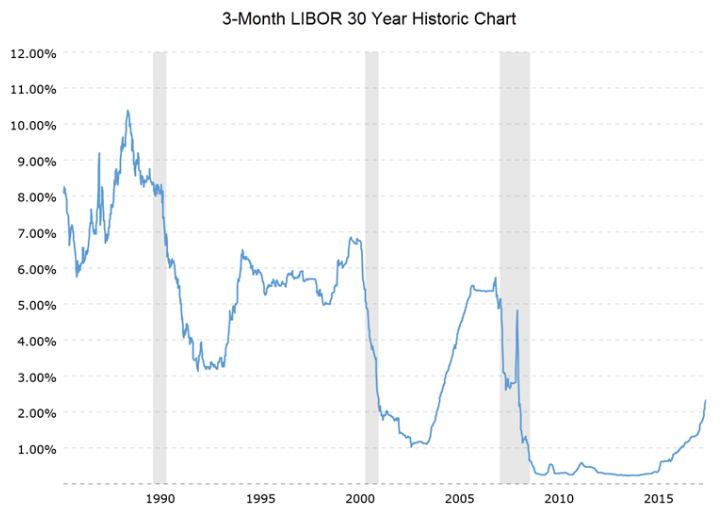

Common sense would tell you that an increase in the LIBOR implies that those top banks comprising the LIBOR panel believe that lending to their fellow financial institutions is becoming riskier; with a significant spike signaling the possibility of economic instability. LIBOR rang an ear-piercing warning bell at the onset of the 2008 financial crisis. Before mid-2007, LIBOR trended with other short-term interest rates such as Treasury yields and the Overnight Index Swap (OIS) rate. But in August 2007, that relationship began to break, signaling the start of liquidity fears that drove the three-month USD LIBOR up to 5.62 percent, from its average of 5.36 percent.

During the same period, the overnight Fed Fund’s policy target rate for the Federal Reserve remained stable. Therefore, the spread between where traders believed the Fed Funds Rate would be and the rate banks would lend unsecured funds to each other started to blow out.

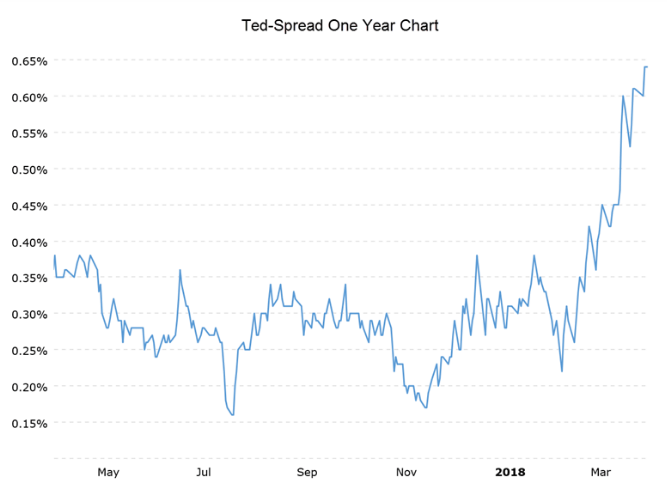

Ted Spread 1-Year Chart (Source: www.macrotrends.net)

The LIBOR-OIS spread (the difference between LIBOR and OIS) continued to rise as concerns about bank liquidity and creditworthiness compelled interbank lenders to pare back funding and demand even higher rates. This spread, a barometer of the health of the banking system, averaged less than 10 basis points from 2005 to mid-2007 but ballooned to 360 bps following the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy.

LIBOR has once again started to rise. During the last two and a half years it increased from 0.3 percent to 2.36 percent; and the pace of that increase has recently picked up steam. It jumped nearly a full percentage point in the last six months—outpacing the moves of the Federal Reserve. One reason is the deluge of short-term Treasury offerings displacing demand for short-term commercial paper, forcing companies to offer higher rates for their short-duration financing. Another explanation for the recent spike is the repatriation of foreign earnings derived from the recent tax law changes.

(Source: 3-Month LIBOR 30-Year Historic Chart)

Regardless of the reasons surrounding LIBOR’s recent spike, its influence in dictating interest rates on roughly $370 trillion in dollar-based financial contracts globally, from corporate loans to home mortgages, makes it extremely painful for the borrowers on the other end. Its recent jump increased all adjustable rate mortgages whose rate is based off LIBOR.

In addition to adjustable rate mortgages and mortgages that have an ARM component, student loans, auto loans and credit cards, are also tied to LIBOR. Most importantly, the LIBOR-OIS spread, which proved to be the canary in the coal mine during the last financial crisis, has just hit its highest level since 2009.

LIBOR provides an essential read to investors about the health of the banking system. It allows them to decipher the risks that exist in the marketplace. But despite LIBOR’s role as a Market Oracle, regulators around the globe are working on a replacement because they believe its key market participants can too easily manipulate it. The scandal that broke in the summer of 2012 arose when it was exposed that banks were falsely manipulating rates in both directions to profit from trades, or to give the illusion that they were more creditworthy.

In the United States, regulators are seeking to replace LIBOR with another acronym SOFR, or the Secured Overnight Financing Rate. A rate based on repurchase agreements–overnight loans collateralized by Treasury securities. Where SOFR relies technically on a broader swath of market participants and is less prone to manipulation, its collateralization to the U.S. Treasury market ensures that it will no longer provide the vulnerability necessary to predict market risk.

The transition away from LIBOR is likely to be a long one due to the necessity to alter millions of legal contracts tied to this rate. But what should concern bankers and market participants more than the cumbersome legality involved in replacing LIBOR is the loss of this essential free-market indicator.

LIBOR will move out of the hands of sophisticated market participants who are risking the health of their bank when they determine this lending rate and remand it into arms of the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve, which may leave banks and investors fewer warning signs and fewer options to protect themselves when the next financial crisis hits.

The truth is governments have complete disdain for markets and are seeking to replace them with increasing alacrity. Governments and Central Banks are nearly always on the wrong side of the economy because they choose to ignore the signals that can be derived from whatever is left from the free market. This is why the Fed kept interest rates at near zero percent for eight years when the economy was no longer on life support and is now raising rates while LIBOR is foreboding an economic slowdown. And this adds to the reasons why the next and even Greater Recession lies just around the corner.

—

DISCLAIMER: This article expresses my own ideas and opinions. Any information I have shared are from sources that I believe to be reliable and accurate. I did not receive any financial compensation for writing this post, nor do I own any shares in any company I’ve mentioned. I encourage any reader to do their own diligent research first before making any investment decisions.

-

Fintech2 weeks ago

Fintech2 weeks agoFintech Alliances and AI Expand Small-Business Lending Worldwide

-

Crypto6 days ago

Crypto6 days agoBitcoin Steady Near $68K as ETF Outflows and Institutional Moves Shape Crypto Markets

-

Fintech2 weeks ago

Fintech2 weeks agoDruo Doubles Processed Volume and Targets Global Expansion by 2026

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoDow Jones Stalls Near Record Highs as Inflation-Fueled Rally Awaits Next Move

You must be logged in to post a comment Login