Featured

There’s more to Fed’s interest rates increase than meets the eye

The Fed is not just raising interest rates, it is also helping banks create a bull equity and bonds markets.

Over the past month, the 10-year Treasury bond yield has jumped from under 3.00 percent to 3.23 percent, sending tremors through the equity markets. By now you’ve heard/read/thought about the usual suspects.

As interest rates move higher, equity investors searching for income finally (finally!) have a viable alternative to stocks.

As interest rates move higher, consumers using borrowed funds to purchase homes, cars, and stuff on credit cards will have to pay more, which should curb their economic appetite.

As interest rates move higher, stock valuations drop because future cash flows (dividends plus capital gains) are worth a little less than they were before.

As interest rates move higher, investors become fearful of how far they will go, making them risk averse.

All of this weighs on equities.

But don’t forget the Fed is doing more than raising rates, and it’s feeding the frenzy.

The central bank created the equity bull market monster out of thin air when it started printing money to buy bonds in March 2009.

By pledging to purchase more than $1 trillion worth of mortgage-backed securities, the Fed gave new life to banks, which owned a bunch of those bonds. But the Fed wasn’t done.

It kept buying more, eventually amassing more than $4 trillion worth of bonds, driving down long-term interest rates and putting more hard cash in the hands of banks. The Fed then paid the banks interest on their cash, guaranteeing bank profits.

Since the Fed didn’t care at what price it purchased bonds, medium and long-term interest rates dropped like a rock. As long as the Fed, with its printing press bank account, kept buying, then rates remained low.

Today, the Fed isn’t buying. And while it isn’t exactly selling, the central bank is shrinking its balance sheet, and that activity is starting to have an effect.

I wrote about this back in the August issue of our flagship newsletter Boom & Bust, “Will the Fed Finally Kill This Bull?”

The Fed’s bond portfolio includes issues that mature anywhere from a month away to 30 years out. Over time, bonds mature. To keep their balance sheet at the same size, the central bank must use the proceeds from bonds maturing to purchase new bonds.

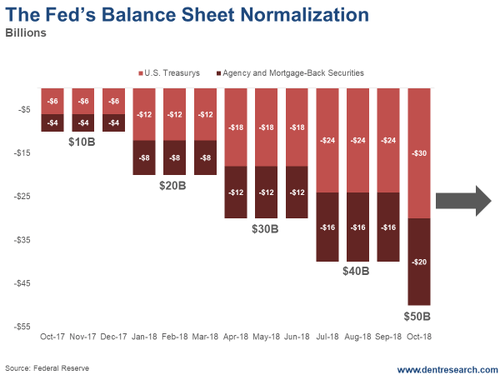

Late last year, the Fed announced plans to shrink its balance sheet by reinvesting fewer bond proceeds than it receives.

They started slowly, holding back $10 billion per month, but have now ratcheted that up to $50 billion per month. Since they began, the bankers have let more than $250 billion worth of bonds roll off, and not replaced them.

©Rodney Johnson

Effectively, the bond market lost the biggest buyer. No one likes it when that happens.

The bankers at the Fed try to move in long waves. They don’t like to change course quickly because it can disrupt the markets by sending mixed messages and sew confusion.

With that as background, investors expect the Fed in December to raise the overnight short-term rate from a range of 2.00 percent to 2.25 percent, to a range of 2.25 percent to 2.50 percent, setting the stage to raise rates another 0.75 percent next year, and reduce their bond holdings by $600 billion in 2019.

How much higher does that push rates? Beats me.

In addition to the positives and negatives listed above, there are several factors that should hold the Fed back next year.

U.S. and global growth should slow, housing and auto sales are weak, and interest rates in other developed nations remain exceptionally low. Oddly, the U.S. remains the “high yield” offering in the developed world, with our 10-year Treasury bond trading 2.60 percent higher than German bunds.

But there is always the wild card of U.S. debt. We’re not issuing a little bit more, we’re pumping out gobs of it as we run $1 trillion deficits. As we sell more debt to finance our profligate spending, we run the risk of flooding the market a bit, weakening demand, and pushing up interest rates.

Our long-term view is that rates go lower as economic activity rolls over, but we could get a spike between here and there as some of the worries above weigh on the markets.

As Harry has often said, bubbles don’t gently deflate, they pop, causing damage to everything around them. The equity and bond markets will be no different.

(Featured image by DepositPhotos)

—

DISCLAIMER: This article expresses my own ideas and opinions. Any information I have shared are from sources that I believe to be reliable and accurate. I did not receive any financial compensation for writing this post, nor do I own any shares in any company I’ve mentioned. I encourage any reader to do their own diligent research first before making any investment decisions.

-

Cannabis5 days ago

Cannabis5 days agoCannabis Use and Brain Aging: What a Major Study Reveals

-

Africa2 weeks ago

Africa2 weeks agoFrance and Morocco Sign Agreements to Boost Business Mobility and Investment

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe TopRanked.io Weekly Digest: What’s Hot in Affiliate Marketing [Discover Cars Affiliate Program]

-

Fintech1 week ago

Fintech1 week agoFindependent: Growing a FinTech Through Simplicity, Frugality, and Steady Steps

You must be logged in to post a comment Login