Crypto

How a new Australian law can affect the crypto and blockchain world

Decentralized encryption is at the heart of all blockchain. But how will blockchain be affected by Australia’s new Asisstance and Access Bill?

On December 6 last year, the Australian parliament voted through a law that would mandate backdoors in all encrypted communications.

Aimed at combating terrorism, the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Bill 2018 still has to be signed into law, but has passed Australia’s legislature. The requirements it places on companies, and individuals at those companies, have led to an outcry in the tech industry and from privacy advocates, in Australia and worldwide.

However, so far little of the debate has focussed on a specific form of encrypted communication: blockchain.

Whether they support cryptocurrencies, general computing or a range of specialized activities, permanent, decentralized encryption is at the heart of all blockchains. It’s what makes them immutable, and what makes it possible to have a network that’s simultaneously secure and decentralized.

So what effect does Australia’s new law have on blockchain?

To understand that, we first need to look at the law itself.

The Assistance and Access Bill explained

The Assistance and Access Bill creates new powers for Australian law enforcement, allowing them to get court orders to require tech companies to insert backdoors in their encryption, teach law enforcement how to hack the users, and not tell their users about it. Additionally, companies will have to reveal the design specifications of their technology on request, and Australian police will be given powers to force anybody to unlock their phone.

The scale of the new powers is explained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Danny O’Brien, speaking to ThreatPost. When users communicate via encrypted messaging apps, says O’Brien, ‘behind the scenes, the company will be required to silently switch you into a group chat. Two of the people in the group chat will be you and your friend. The other will be invisible, and will be operated by the government.’ iMessage would be compelled to do something similar with devices.

These powers are intended to bypass technical issues relating to end-to-end encryption, and thus combat terrorism and crime.

How does all this apply to the blockchain?

Blockchains are all based on decentralized encryption. The power to compel Ethereum to publish its code can’t result in access to the accounts of EVM users, for instance. The code is open source anyway.

There’s no single, centralized entity against whom pressure can be exerted to oblige them to allow access: each user owns their own credentials, so access powers would have to be exerted against individual users.

With that in mind, Australia has two options. One is to create exceptions for blockchain, which would include communications and data storage taking place on the blockchain. That’s a huge problem from the point of view of Australia’s lawmakers, because the purpose of the law is to access and police communications. Making a loophole for Cyphr, Crypviser, Echo and Dust would leave the law toothless.

The other option is to leave the law as it is, and to ban blockchain-based tools and services.

How will that look?

Cryptocurrencies and the Bill

Cryptocurrencies could be seriously affected by the new regulations. Obviously, any law that bans encryption is de facto hostile to a currency based on encryption. But most cryptocurrencies are built on structures so decentralized that no authority can seize control of them and turn them into fiat currencies by proxy.

What could happen is sharp restrictions on access to unregulatable websites. The new law gives wide-ranging website-blocking powers which could be used to block access to exchanges, particularly decentralized exchanges which by their nature can’t be effectively regulated by a third party.

It’s possible that Australians could circumvent the new regulations using tools like VPNs, as citizens of China and other authoritarian regimes do. But this would move cryptocurrency trading into a grey-to-black market, reducing its appeal, damaging its image and risking an outright ban.

Business and trade are moving over to the blockchain

Australia may have locked itself out of major business changes. The global trade network is quietly turning to the new technology, hoping to improve record-keeping and apply blockchain for supply chain management. Infrastructure, supply and other vital but unglamorous spaces are turning their attention to the technology too. Lured by the promise of grid balancing in real time, Technavio estimates that blockchain will see a 65% CAGR in uptake until 2023 in the energy sector alone.

Meanwhile, it’s tough to see how a decentralized technology like TradeLens can be kept compliant with the Assistance and Access Bill. And with shipping giant Maersk, IBM, and a slew of others signing up for the scheme, it looks as if Australia may be on the verge of accidentally outlawing the next development in global trade.

Dapps: the next big digital growth market

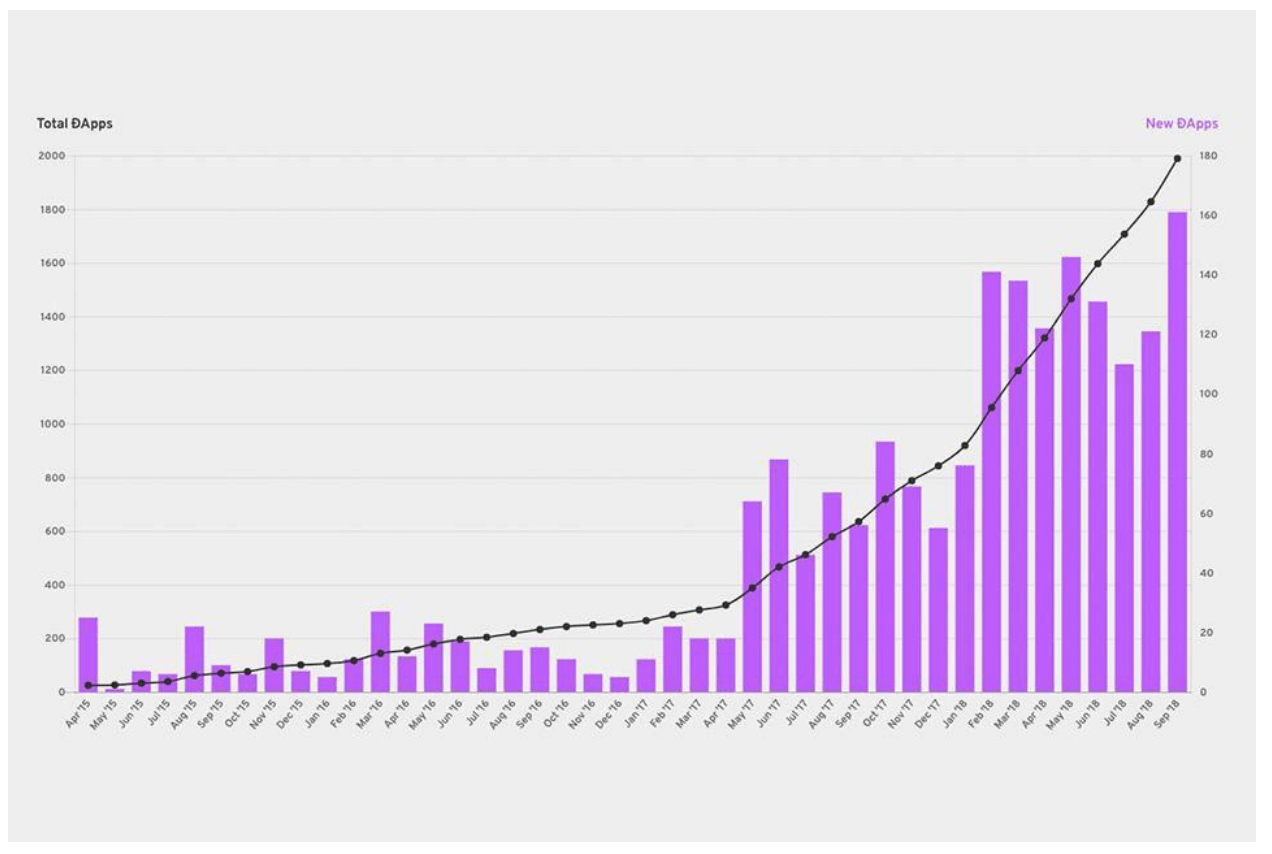

Dapps — Decentralized applications — take the promise of general-computing blockchain and build on it, creating applications that run entirely on the blockchain. It’s a rapidly growing space:

(Source)

Currently, there are around 1,900 Dapps worldwide with a combined user base of about 12,000. Those numbers might be low, but as the graph above shows, they’re growing rapidly. And it’s worth remembering that in 1991, there was just one website on the world wide web. Now there are over a billion. Not every new technology takes off like this, of course; but the future for Dapps looks bright. And Australia’s new encryption law could kill the country’s Dapp market entirely.

Communications for global companies

In particular, encrypted communication Dapps like Cyphr are totally inviolable by these new powers. Will the Assistance and Access Bill reduce their popularity? It seems unlikely, though the loss of markets might affect some newer businesses in the space.

What it might do is make them illegal to use, or illegal to develop. As more and more companies look for secure means of communication, that could result in Australian businesses, contractors and employees being excluded from communications. When distributed teams, portfolio careers and conglomerations of contractors and suppliers are becoming more common, this could hit the Australian economy.

Beyond Australia

All these effects won’t be limited to Australia. Blockchain has increasingly become a normal part of life for businesses and individuals, and behind the scenes, it has been quietly becoming indispensable to infrastructure. Australia could still cancel its encryption law, or amend it. But if it goes ahead and makes effective encryption illegal, what effect will that have on blockchain globally?

It’s difficult to say, because the law is notoriously ambiguous. Called ‘technically vague’ by phys.org, its provisions seem so open-ended to some that many security experts agree with Harvard’s Bruce Schneier: ‘This is a technological law written by non-technologists and it’s not just bad policy. In many ways, I think it’s unworkable.’

Its effects beyond Australia could be complex. It’s been viewed as a ‘beachhead,’ for a more rigorous legislative approach to encryption worldwide. But the effect could be to make other nations’ governments recoil from banning blockchain, especially since worldwide trading and communications networks have already begun to rely on the technology.

In many cases, it’s not just the private sector: governments have reached for blockchain solutions to use in land registries, patent offices and many more functions.

Conclusion

Regulation of decentralized systems was always going to pose a challenge, especially where regulators don’t have a firm grasp on the underlying technology. But there’s a good chance that Australia’s new encryption laws could actually lead to better, rather than worse regulation. Experience of trying to exclude blockchain from business, personal and governmental life could lead future legislative efforts, in Australia and elsewhere, in a more benign direction. In the meantime, it’s still possible that Australia won’t enact the current Bill as written. Even if it does, it doesn’t outlaw the use of encrypted applications or of blockchain-based tools and services, so for now, keep using them.

(Featured image by DepositPhotos)

-

Crowdfunding2 weeks ago

Crowdfunding2 weeks agoRE-Lender, a Crowdfunding Lending Platform with over 40 Million Raised, Obtains EU License

-

Biotech3 days ago

Biotech3 days agoSartorius Stedim Biotech Attempts a Modest Rebound After Plunge

-

Impact Investing1 week ago

Impact Investing1 week agoHuma Therapeutics Limited Has Closed a Series D Financing of Over $80 Million

-

Crypto1 week ago

Crypto1 week agoUS Spot Bitcoin ETFs See Record Inflows: What’s Behind It?

You must be logged in to post a comment Login