Business

What can investors learn from the best hitter in the history of baseball?

Williams became a babseball legend because he approached the game analytically, studied his opponents and most importantly, practiced.

Williams understood where his “happy zone” was. Investors need to have the self-awareness to know when the market is favoring their specific trading style.

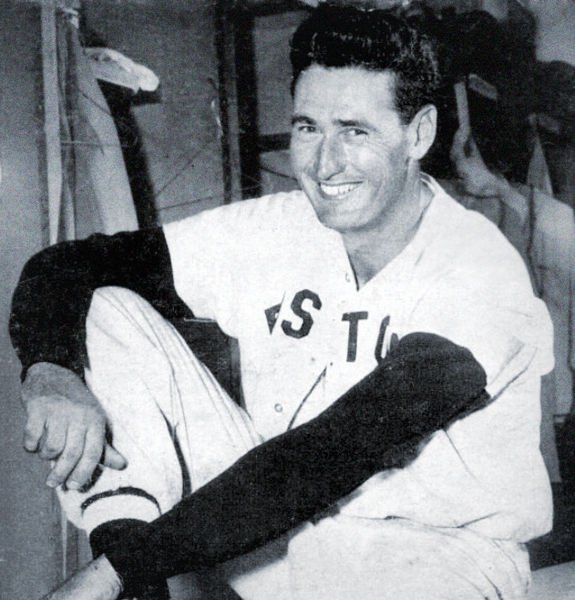

Ted Williams was arguably the best hitter in the history of baseball.

The Boston Red Sox left fielder finished his 19-year professional career with a lifetime batting average of .344 and an on-base percentage of an incredible .482, and this despite taking time off in the prime of his career to fight in World War II and the Korean War.

He also won the Triple Crown, meaning he led the league in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in… and he did it twice.

To put that in perspective, there’s only been 16 Triple Crown winners in the history of baseball, and two of those belong to Williams. And to cap it off, Williams was also the last Major League Baseball player to bat .400 in a season.

It’s safe to say that Ted Williams knew a thing or two about hitting a baseball.

And he was generous enough to share some of his secrets in his 1986 book, The Science of Hitting, which I strongly recommend for any baseball fan with an appreciation for history.

Interestingly, we can apply a lot of his same insights to investing.

To start, both baseball and investing are “sports” in which it pays to study. Sure, Williams was probably born with better eyesight and better reflexes than you or me. But that’s not why he was the greatest hitter in history.

Williams was the best because he was willing the approach the game analytically, study his opponents and—perhaps most importantly—practice.

More than a half-century before Billy Beane used statistical analysis to revive the struggling Oakland Athletics (as recounted in Michael Lewis’ book Moneyball), Williams might have been the first “quant” in professional sports.

Williams carved the strike zone into a matrix: seven baseball lengths wide and 11 tall. His “happy zone” – where he calculated he could hit .400 or better—was a tiny sliver of just three out of 77 cells. In the low outside corner of the strike zone—Williams’ weakest area—he calculated he’d be a .230 hitter at best.

The “happy zone” will vary from batter to batter, but Williams understood exactly where his was, and he wouldn’t swing if the pitch was outside of his zone.

Likewise, investors need to have the self-awareness to know when the market is favoring their specific trading style.

When it is, it makes sense to swing for the fences. And when it’s not, you don’t have to swing at all.

Williams was notoriously patient and disciplined at the plate, which is why his on-base percentage was so high.

He had control over his ego and his emotions and wouldn’t swing because the defense – or even the spectators – was taunting him. He finished his career behind only Babe Ruth in bases on balls (walks).

And in investing, it might be easier. You can watch pitches go by until you see one you like. As Warren Buffett famously said, there are no called strikes in investing.

While professional investors have enormous career pressure to look like they’re “doing something,” individual investors don’t have to worry about a boss firing them. They can afford to be patient and wait for a perfect trading setup.

Williams, an eventual Hall of Famer, was chastised in his day for talking too many walks by none other than the legendary Ty Cobb. Well, frankly, Williams could call “scoreboard” on Cobb.

Cobb finished his career with a slightly higher batting average (.366 versus .344) but his on-base percentage trailed Williams’ by a much wider margin (.482 versus .433).

But perhaps the best lesson from Williams is this:

If there is such a thing as a science in sport, hitting a baseball is it. As with any science, there are fundamentals, certain tenets of hitting every good batter or batting coach could tell you. But it is not an exact science.

While it pays to take a detached, scientific approach to investing, it is absolutely not an exact science. Given the role that human emotions play, it’s probably closer to a social science like psychology than to a hard science like chemistry or physics.

That’s why it’s always important to give yourself a little wiggle room when you invest, what Benjamin Graham called his margin of safety. Structure your trading so that being “mostly right” is good enough.

That’s the approach I take in my income service, Peak Income. By focusing on high-yielding funds, I don’t have to get the timing exactly right, and, like Williams, I’m not swinging at every part of the strike zone.

I’m paid handsomely via high dividends to wait for my value thesis to play out. And by buying funds trading at deeper-than-usual discounts to net asset value, I massively increase my margin of safety.

What’s more, the bends and twists of the bond market over the past few years have given me quite a few fat pitches to swing at.

—

DISCLAIMER: This article expresses my own ideas and opinions. Any information I have shared are from sources that I believe to be reliable and accurate. I did not receive any financial compensation in writing this post, nor do I own any shares in any company I’ve mentioned. I encourage any reader to do their own diligent research first before making any investment decisions.

-

Crypto2 weeks ago

Crypto2 weeks agoXRP vs. Litecoin: The Race for the Next Crypto ETF Heats Up

-

Crypto1 day ago

Crypto1 day agoCrypto Markets Surge on Inflation Optimism and Rate Cut Hopes

-

Biotech1 week ago

Biotech1 week agoSpain Invests €126.9M in Groundbreaking EU Health Innovation Project Med4Cure

-

Biotech4 days ago

Biotech4 days agoAdvancing Sarcoma Treatment: CAR-T Cell Therapy Offers Hope for Rare Tumors

![Kevin Harrington - 1.5 Minutes to a Lifetime of Wealth [OTC: RSTN]](https://born2invest.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/kevin-harrington-400x240.jpg)

![Kevin Harrington - 1.5 Minutes to a Lifetime of Wealth [OTC: RSTN]](https://born2invest.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/kevin-harrington-80x80.jpg)

![RDE, Inc. [ OTC: RSTN ] is set to soar in a perfect storm](https://born2invest.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/pexels-burak-the-weekender-187041-400x240.jpg)

![RDE, Inc. [ OTC: RSTN ] is set to soar in a perfect storm](https://born2invest.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/pexels-burak-the-weekender-187041-80x80.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment Login