Business

A brief history of Augmented and Virtual Reality (AR/VR)

Given that VR/AR is all the rage now, you’d be forgiven for thinking it’s something new. But, the reality is, the first VR device was released in 1962, and the roots of the concept stretch right back to 1938. Of course, developments were few and far between, with available computing power acting as a major limiting factor. But that’s all changed now as we sit on the precipice of the VR/AR age.

While Extended Reality (XR) is nothing new, the sector has garnered a lot of attention for itself in recent years. With the first publicly available devices emerging as far back as the early-sixties, when Morton Leonard Heilig released the Sensorama, it has certainly taken some time for it to come of age as a serious investment opportunity. But now it seems that its days as a mainstream technology have finally arrived. The days of crazy looking Virtual Reality (VR) gizmos and gadgets are coming to an end, and companies like XRApplied are rolling out pocket-friendly and practical applications that find their use in everyday life.

It has been a long road getting Virtual Reality to the point where it is today

While computers managed to take over the world at a blinding pace, Virtual Reality (and, later, Augmented Reality) has taken its time. Providing some perspective on the different rates of development, Alan Turing first published his work on the Turing Machine (a theoretical computer capable of running any arbitrary algorithm) in 1949. By the 1960s, computers were, amongst other truly useful things, charged with landing on the moon (and with getting there and back safely).

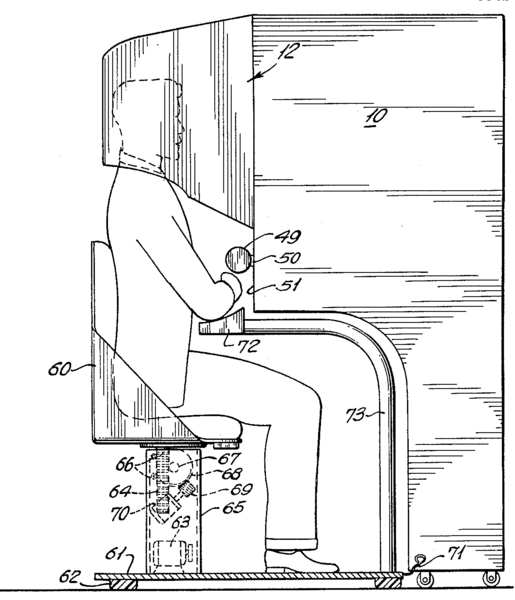

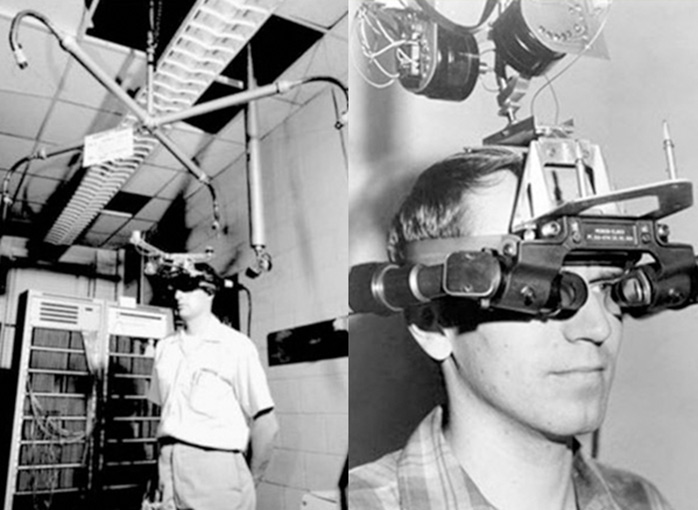

Contrast this with Virtual Reality, which was first articulated by Antonin Artaud in his 1938 book The Theatre and Its Double. By the end of the sixties—the same time computers were landing on the moon—Bob Sproul’s Sword of Damocles—the first “head-mounted” Virtual Reality display—debuted, letting users look around some basic wireframe rooms, and that was about it. But it wasn’t called the Sword of Damocles for nothing. Here, head-mounted merely implies that one attaches their head to the device. And yes, one attaches their head to the device, not the device to their head. It was so bulky that it actually had to be suspended from the ceiling, and its “formidable” appearance and its perceived potential to cause harm to its users inspired its name.

Allowing for homophones, the first iPhone was a Virtual Reality headset: the EyePhone

Progress in VR continued at a snail’s pace following its 1960s birth. There was little interest in Sensorama-type experiences and, even if the computing power needed to render worthwhile VR environments was available, the ungainly nature of devices like the Sword of Damocles rendered them rather impractical.

But things began picking up in the 1980s, and true Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) became a reality. These developments came amidst a flurry of futuristic thinking, with one of the first companies to sell VR tech products (VPL Research) creating devices that weren’t too far removed from the VR gear we all know and love today.

Amongst the suite of products making up VPL’s range was the EyePhone: a Virtual Reality HMD that, visually, is only differentiated from the devices we see today by its solid around-the-head fitting and its charming beige-dominant color scheme. Showing huge progress from its forefather, The Sword of Damocles, the device also managed to pack in motion-sensing without the use of physical tethers to fixed points.

But, while VPL’s ambitions were futuristic (they also produced the motion-sensing “DataGlove” and “BodySuit”), the technology of the 1980s wasn’t where it needed to be for VR to advance. Because of these limitations, the original EyePhone device was only able to operate at six frames per second—a rate that left its simulations looking more like animated gifs and less like reality. It’s also worth noting that the cost of the EyePhone system (which needed dedicated computers to run it) was a cool $250,000.

Despite the fundamentals being in place, much needed technology was not

With much of the essential groundwork for Virtual Reality now laid out, it would seem that it was ready to take off in the nineties. But, despite having the fundamentals in place for HMDs and other motion-sensing devices, the graphics processing demands of Virtual Reality were not easily met by available computing power.

But this didn’t stop companies from trying to profit from this futuristic technology, with major gaming companies like Sega and Nintendo hyping up their respective product developments in VR. Ultimately, however, this led to disappointment.

After announcing the upcoming release of its VR headset in 1991, Sega quietly removed it from any launch programs after a handful of appearances at gaming fares. Sega’s claims at the time were that it simulated reality far too well, thus putting users at risk, but initial user reports of rapid onset motion sickness are a likely contributing factor to its quiet disappearance.

But more than this, the graphics at the time were still too rudimentary, as evidenced by Nintendo’s 1995 answer to Sega’s VR hype; the Virtual Boy. With crude graphics rendered in monochrome red, the experience left a lot to be desired. One user in a recent YouTube video even describes playing 2D Mario on a regular Nintendo console from that era as being “more 3D” than the “glasses or whatever the hell thing that was.” This same user describes the Virtual Boy Mario as looking like a “Flat Stanley.”

After years of fits and starts, Oculus and Google Glass arrive, finally giving some legitimacy to Augmented and Virtual Reality

After decades of hardware-impeded development, the 2010s were the years that VR and AR finally began to gain some legitimacy. Oculus and Google Glass caused a storm, finally delivering on the promises that VR had been making for decades. (Even if Google Glass did miss the mark and suffer from a lack of traction.) But, even with hardware finally coming of age, there were still some hesitations.

In early 2012, just before the Kickstarter campaign that launched Oculus into its VR success-story trajectory, founder Palmer Luckey was still skeptical. Writing on his hopes and dreams for the Oculus project, Palmer said “I won’t make a penny of profit off this project, the goal is to pay for the costs of parts, manufacturing, shipping, and credit card/Kickstarter fees with about $10 left over for a celebratory pizza and beer.” Little did he know that Facebook would pay over US$2 billion to acquire it just two years after making this statement.

After a decade of getting the hardware in order, today we’re seeing a rapid acceleration in Virtual Reality

As hardware began to mature over the course of the 2010s, mainstream interest in VR and AR technologies began to develop. At first, this was largely limited to VR, especially gaming; initially, no one really knew what to do with Augmented Reality developments like Google Glass. But as early-adopters began experimenting with what Augmented and Virtual Reality could do, a snowball effect began to emerge.

Now, as the first year of a new decade comes to an end, this acceleration has brought VR and AR up to such a velocity that we no longer have to wait years for breaking news in Virtual and Augmented Reality developments. Today, as demand for VR and AR tech innovations increases exponentially—for everything from therapy through to training and quality control in businesses—companies like XRApplied are delivering… quickly.

Advancements that used to take decades now happen seemingly overnight, meaning that there’s something VR- or AR-related happening in the news every day. To help themselves (and everyone else) stay on top of it all, XRApplied created a VR and AR news aggregation app which acts as a sort of highly curated RSS feed. With this app, the latest AR and VR news developments are neatly sumarized in a digestible format, making it the perfect continuation to the VR history books that we’ve traversed today.

—

(Featured image by Stephan Sorkin via Unsplash)

DISCLAIMER: This article was written by a third party contributor and does not reflect the opinion of Born2Invest, its management, staff or its associates. Please review our disclaimer for more information.

This article may include forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements generally are identified by the words “believe,” “project,” “estimate,” “become,” “plan,” “will,” and similar expressions. These forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks as well as uncertainties, including those discussed in the following cautionary statements and elsewhere in this article and on this site. Although the Company may believe that its expectations are based on reasonable assumptions, the actual results that the Company may achieve may differ materially from any forward-looking statements, which reflect the opinions of the management of the Company only as of the date hereof. Additionally, please make sure to read these important disclosures.

-

Business2 weeks ago

Business2 weeks agoFed Holds Interest Rates Steady Amid Solid Economic Indicators

-

Fintech1 week ago

Fintech1 week agoMuzinich and Nao Partner to Open Private Credit Fund to Retail Investors

-

Crowdfunding2 weeks ago

Crowdfunding2 weeks agoSwitzerland’s Crowdfunding Market Remains Stable – Without Growth

-

Crypto3 days ago

Crypto3 days agoBitcoin Traders on DEXs Brace for Downturn Despite Price Rally