Business

How to manage an ESCO relationship

Outsourcing services such as ESCO is useful in the management of energy-related public services and energy cost savings.

Managing your relationship with an energy service company (ESCO) is an art and a science. We will focus here on the good theory of how to do it successfully, if (and only if) your organization has decided that an ESCO relationship is helpful because you don’t have and don’t want to have the in-house resources to develop energy projects in-house.

Motherhood and apple-pie: Follow the money

Before and after anything, energy retrofitting is all about finance and economics, and since energy is usually one of the bigger bills in an organization. So, forget any other arguments. The only objective in your organization should be maximizing enterprise value and optimal capital allocation. Relatively speaking, good energy retrofit projects tend to have high alpha and low beta, i.e. they produce above average returns with below average risk. The reason the risk is below average is that these are intra-marginal investments: you are moving energy from liabilities to assets. And the reason the returns tend to be above average is in large part exactly because the risk is low.

To be specific, you already have the risk of energy bills, and while specific energy rates are notoriously hard to predict, it is always possible to establish a reasonable bandwidth of a high and low and most likely future price scenario you can agree on. So, from a financial point of view, your retrofit endeavors are a risk mitigation effort. For specific environmental parameters, you need to look at both the politics which can impose certain measures and the strategic views of your organization. These measures need to be made explicitly.

This is to say that if current politics tolerate pollution, as is now happening in the US, your organization may well believe that in the long run some form of pollution tax will return with a vengeance, and you would prefer to invest in that. These are all assumptions you can quantify, and discuss up front before decisions are made.

Once you have those basic background assumptions documented, the next thing to realize is that the basic pitfall with an ESCO relationship is that it could backfire if their objectives—making the most money from the project, conflict with the objectives of your organization. Therefore, what matters is that the project is defined right at the outset before it is turned over to an ESCO for execution.

The first decision: What is the project

You can’t just leave it to an ESCO to pick your project for you. The worst thing to do is to optimize a secondary variable. The simple example always is that if you have 20lbs of sugar in the pantry, and sugar is on sale that week, you do not need another 5 lbs of sugar and certainly not if you’re me, who never uses sugar. Yet this is the mistake that is made too often with energy projects, in particular, if they are undertaken because of this or that incentive.

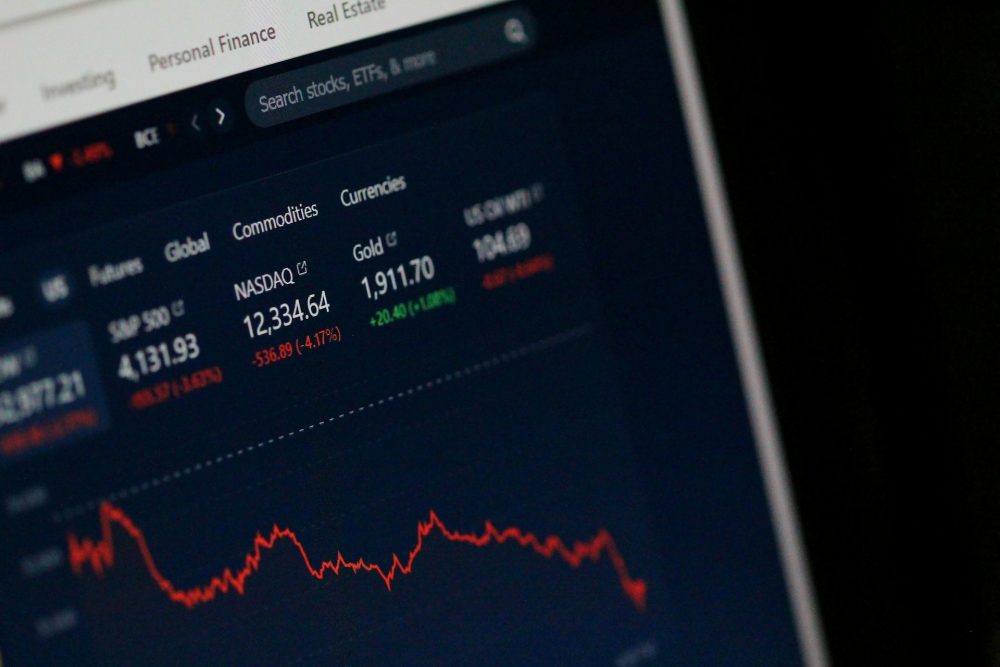

Before selecting an ESCO service, make an analysis of the energy needs that suit your company best. (Source)

Your organization needs to evaluate its technology options first, and once you have done your basic evaluation, you can go about selecting an ESCO, and you could even invite them in to criticize your technology evaluations—they may know something you did not. The critical point here is to end up with high confidence that you have selected the right technology.

Once this major assumption is out of the way, a normal ESCO contract is basically a deal where you are willing to give up 50 percent of the energy savings for the duration of the contract, in exchange for a contractor who sub-optimizes that project for you. The things you still need to watch out for is how value is created, and how contract periods may distort the choices.

Let’s say you decided that a realistic project lifespan was 30 years, but you were going to let an ESCO contract for 20 years. To make it more interesting, energy storage was going to be an option and there were technology options for batteries with a 10-year warranty, a 30-year warranty and a 50-year warranty. Under your 20-year ESCO contract, the battery with the 10-year contract may well appear the cheapest, whereas to you who own the building ad infinitum the 50-year battery may be a better choice. Or, another example, one that is near and dear to my heart, what if the payback of power conditioning and energy efficiency were clear with a 30-year lifespan but less so under your 20-year ESCO contract. You would want to be very clear that the 30-year model is the basis of the evaluation.

Fortunately, many energy efficiency and power conditioning measures are usually available that have very short paybacks, and will therefore reduce the overall project payback, and indeed they would improve the bottom line for the ESCO as well as for your organization.

In short, as long as you keep a critical eye on the correct decision framework, an ESCO relationship may work for you if you are explicitly clear that the sacrifice of 50 percent of the savings is worth it to you to pay for their greater expertise and minimize your need to manage the details—thereby reducing your overhead. If the project is not well defined at the outset, you may end up increasing your overhead and having an expensive fight with the ESCO one day, something that is not unheard of in that industry. As usual: caveat emptor.

—

DISCLAIMER: This article expresses my own ideas and opinions. Any information I have shared are from sources that I believe to be reliable and accurate. I did not receive any financial compensation in writing this post, nor do I own any shares in any company I’ve mentioned. I encourage any reader to do their own diligent research first before making any investment decisions.

-

Markets2 weeks ago

Markets2 weeks agoThe Big Beautiful Bill: Market Highs Mask Debt and Divergence

-

Africa2 days ago

Africa2 days agoORA Technologies Secures $7.5M from Local Investors, Boosting Morocco’s Tech Independence

-

Markets1 week ago

Markets1 week agoA Chaotic, But Good Stock Market Halfway Through 2025

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoThe Dow Jones Teeters Near All-Time High as Market Risks Mount

You must be logged in to post a comment Login